Writers can be a competitive bunch and can say nasty things about others in their profession. A good barb needs to be pithy and clever. Here are a few of my favorites.

Showing posts with label famous authors. Show all posts

Showing posts with label famous authors. Show all posts

Thursday, March 12, 2020

Thursday, August 29, 2019

Author Interview at NFReads.com

Today, NFReads published my author interview. They ask good questions, so if you want to know my dark secrets, take a gander. Just kidding. I kept my darkest secrets in a closet under two tons of rubbish.

P.S. Don't forget to pre-order No Peace, A Steve Dancy Tale

P.S. Don't forget to pre-order No Peace, A Steve Dancy Tale

Sunday, March 18, 2018

Mark Twain's 10 Writing Tips

Curiosity.com

published a list of writing tips from Mark Twain. Now, Twain never actually

published a list, but his letters provided plenty of tips that just needed to

be gathered up in one place.

1. "Write without pay until somebody offers to

pay."

2. "Don't say the old lady screamed. Bring her on and

let her scream."

3. "Great books are weighed and measured by their style

and matter, and not the trimmings and shadings of their grammar."

4. "The time to begin writing an article is when you

have finished it to your satisfaction."

5. "If I had more time, it would have been

shorter."

6. "The more you explain it, the less I understand

it."

7. "Substitute 'damn' every time you're inclined to

write 'very.' Your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it

should be."

8. "The difference between the right word and the

almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning

bug."

9. "Use plain, simple language, short words, and brief

sentences... don't let fluff and flowers and verbosity creep in."

10. "As to the adjective: When in doubt, strike it out.”

Good advice, but I believe scrutinizing Twain’s castigation of

James Fennimore Cooper provides even more guidence. Among other things, Twain wrote “Cooper's art has some

defects. In one place in "Deerslayer," and in the restricted space of

two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out

of a possible 115. It breaks the record.”

If the criticisms of Cooper were

rewritten as positive statements, they would make a great guide to great

writing. Which I took the liberty of doing here.

You may also want to check out my catalog of writing advice

from the masters.

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Building a Franchise

Platforms, branding, franchise, fans, discoverability. There

are many words bandied about that all represent the same thing: how does an

author build a base of loyal readers. Forbes

recently published an article by David Vinjamuri titled: The

Strongest Brand In Publishing Is ... The premise of the article is that

brand is more important than platform. He argues that if platform was key,

celebrity books would all be successful. One of his interesting observations is

that consumers are willing to pay a 66% premium for a book by a favorite author

over an unknown author. This means favorite authors sell more books at a higher

price. It does seem that brand loyalty is more important than a social media

platform.

So, how do you build a literary brand? Although not called

out specifically by Vinjamuri , it appears that characterization is the most

crucial element. Granted, authors need to know how to write and tell a good

story, but readers develop the greatest loyalty to a character. A good character draws readers back to an author faster than fame, storytelling, or exceptional

writing skill.

The strongest brand in the most recent Codex survey is Jack Reacher, who is a character created by Lee Child. Reacher is completely different from the stereotypical thriller hero. Jack Reacher novels have sold

over 70 million copies, making Child comfortable enough to buy a Boeing

product. Vinjamuri writes, “Child carries a higher percentage of his readers

with him to each successive book than any other bestselling author.”

If you’re interested in finding out how Child accomplished this, get it from the horse’s mouth. In Vinjamuri’s article, Child gives three perceptive reasons why Reacher has strong brand loyalty.

Now, if I can just get Steve Dancy an introduction to Jack Reacher, all will be right in the world.

If you’re interested in finding out how Child accomplished this, get it from the horse’s mouth. In Vinjamuri’s article, Child gives three perceptive reasons why Reacher has strong brand loyalty.

Now, if I can just get Steve Dancy an introduction to Jack Reacher, all will be right in the world.

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

Outline a Novel?

|

| Joseph Heller's Outline for Catch 22 |

How much

planning should there be for a novel? Should there be an outline? Should you

compose character sketches? How much research after the first draft?

My answer to

all of these questions is that it depends.

Tempest at Dawn is a novelization of the

constitutional convention. Prior to writing the first draft, I had visited

Philadelphia twice, complied biographical information for the primary

delegates, built a small library about the convention and eighteenth century

lifestyle, created a highly detailed convention timeline, extensively marked-up

Madison notes, acquired an 1787 map of Philadelphia, and secured architectural

layouts for the State House. I knew the content of every chapter well before I

started writing.

The Shopkeeper is the first in the Steve Dancy

western series. I did zero research prior to the first draft, nor did I have an

outline. Although I had nothing on paper, I mentally knew the beginning and end

of the story, but how I would get from one point to the other was vague. I also knew my main character and his

sidekick, but the other characters evolved as the story progressed. After I

finished the first draft, I collected some friends and did a road trip through

Nevada to explore locales for the story. In fact, I asked my ghost town

enthusiast friend to find me a mining camp within a few days horse-ride of

Carson City. She did, and that is how the story opened in Pickhandle Gulch.

After I did the Nevada research and investigated mining in the state, I rewrote

the book from beginning to end.

These are

two preparation extremes. Why the difference from the same author? Tempest at Dawn was a dramatization of

arguably the most important event in the founding of the United States. Accuracy was paramount. It had

to survive the scrutiny of professional historians, which it did with flying

colors. The Shopkeeper was pure

fiction with historical detail limited to locale and nineteenth century

lifestyle. The story was paramount. I

wanted to get the story and the characters down on paper before interweaving

detail that would make the novel feel right for the Nevada frontier.

The bottom

line is that I do what feels right for the project. I don’t believe there is a

right and wrong way. There is good advice out there from successful writers,

but I believe good writers do what is natural for them. So … my advice is to go

with your instincts.

Tuesday, January 14, 2014

Crazy Book Dedications

|

| Nelson DeMille |

The Barnes

and Noble Book Blog published a

list of 25 odd, clever, or humorous book dedications. Ever since Cathedral,

Nelson DeMille has been one of my favorite authors. His dedication for Wild Fire is my

favorite, although it’s attached to my least favorite DeMille book. I

remember when Wild

Fire was first published, I laughed when I read the dedication. Unfortunately, the rest of the

book was a disappointment.

I have never

tried to be clever with my dedications. Most of them simply state one or more

family member's first names. I did get verbose with Leadville,

dedicating the book in the following manner to my twin grandsons.

For Leo and Eli

Hey boys, I finished Leadville in the

hospital when you were born

The dedication

for Anansi

Boys, by Neil Gaiman is another favorite.

You know how it is. You pick up a book, flip to the dedication, and find that, once again, the author has dedicated a book to someone else and not to you.

Not this time.

Because we haven’t yet met/have only a glancing acquaintance/are just crazy about each other/haven’t seen each other in much too long/are in some way related/will never meet, but will, I trust, despite that, always think fondly of each other!

This one’s for you.

With you know what, and you probably know why.

Gaiman’s

dedication reminded me that I used to subscribe to Forbes to see my name on the cover of their 500 Richest People in America issue. Of course it

was only on the address label, but proximity to all those successful people

filled me with hope for the next year. If you would like to help me fulfill my

dream of obscene wealth, please buy one of my books. Thank you and I promise to

dedicate my next book to you.

Sunday, January 12, 2014

How to Sell a Half Million Books—After You’ve Been Dead 100 Years

Dead people

publish new books all the time. Some of these books are unfinished

manuscripts. Others are ghostwritten from scratch to take advantage of a famous

name like Robert Ludlum. But there is one book composed by the actual author

that was purposely withheld from the market for one hundred years, and after release,

sold over a half million copies. Now that’s quite a feat.

|

| Click to buy at Amazon |

The author,

of course, is Mark Twain, and the book is his autobiography … Volume 1. (The

New Yorker has a fine article about

Twain’s autobiography.) The second volume has just been released and is also

projected to sell well.

Twain specified in his will that his autobiography

could not be published until 100 years after his death. He claimed that time would

heal the wounded egos of those he assaulted. There is a lot of vitriol aimed at long forgotten people, but the only controversial aspect of his own life is an atheism well known by his contemporaries. In typical Twain humor, he wrote, “I have thought of fifteen

hundred or two thousand incidents in my life which I am ashamed of, but I have

not gotten one of them to consent to go on paper yet.”

The delayed

publication was a grand publicity stunt by one of our nation’s foremost

self-promoters. Twain believed, no, he knew that the great great grandchildren

of his current readers would be interested in his life. He expected immortality

of an earthly variety … and he was right.

The

meandering style of the book has not garnered good reviews. Twain wrote that other

autobiographies “patiently and dutifully follow a planned and undivergent course.”

His own, by contrast, is “a pleasure excursion.” It “sidetracks itself anywhere

that there is a circus, or a fresh excitement of any kind, and seldom waits

until the show is over, but packs up and goes on again as soon as a fresher one

is advertised.”

Related Posts

Wednesday, January 8, 2014

Can Novelist see the past better than historians?

I recently

read Stephen Hunter’s, The Third Bullet,

which is a novel about the John F. Kennedy assassination. Through the years, I

have read a half dozen nonfiction books on the assassination. Although I didn’t

completely accept the conspiracy motivation presented by Hunter, I think he

made a better case for a second shooter than any of the other books on the subject.

Hunter clearly sees the incongruities in the official portrayal of events,

imagines alternative scenarios, and then figures out what most likely happened

given the existing record. He does an exceptional job while presenting a

standard Bob Lee Swagger suspense thriller.

The Third Bullet made me think: Do novelists see the

past better than historians?

I’m

prejudice, but I believe so. Historians search for facts, facts that can be

verified with attributable sources. They need those tiny footnotes for credibility.

Novelists naturally go to the character of people, especially if those people are

orchestrating events. Novelists search for motivation. The novelist looks for

the thread of a story, which will always be about people and what drives them. They

focus on why, not what. Historians at times engage in

conjecture, but good historians put plenty of qualifiers around anything that

cannot be proven with hard evidence.

Everything

that happens in the world is not documented. Worse, much of what is recorded is

inaccurate. Politicians, businessmen, and luminaries dissemble, obfuscate, and

sometimes outright lie. But if someone of importance spoke it or wrote it and

it becomes old enough, it takes on the stature of a documented fact. This is

where a good novelist has an advantage over the historian: what historians see

as documentation, the novelist looks at with a skeptical eye. The novelist

imagines the circumstances that might have caused that particular piece of

evidence to be created. And the novelist does not always come to the same

conclusion as the historian.

My book, Tempest at Dawn is a dramatization of

the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Although George Washington was president of

the convention, he only spoke one time at the very end. Since there is no

record of Washington being engaged in the proceedings, most historians dismiss

him as a figurehead. I looked at Washington’s character and knew he would never

sit on the sidelines, especially when it looked like the entire nation was

about to collapse. Once I came to that conclusion, I found ample evidence of

him working behind the scenes. Why would he work secretly? My guess is that he didn’t

want to appear to be architecting the new government he would undoubtedly lead.

I could be wrong … but I don’t think so.

I believe a

good novelist can digest facts, get to know the character of the players, and draw

respectable conclusions about what probably happened. The novelist can make

leaps of logic that would tarnish the reputation of an academic scholar. It’s

true that many novelists throw facts to the wayside and tell the story the way

they wanted it to happen. Stephen Hunter is not one of those types of authors.

His books are fictional, but grounded in solid research.

Here’s the

bottom line, authors can’t write novels about historical events without

historians, but historians can get along quite fine without novelists. So,

thank you to all the historians who have helped me write better books.

Monday, January 6, 2014

Six Makes Magic

My wife and

I just finished a perfect vacation in Southern California. Our daughter and son’s

families have returned to their homes and everything is now calm and still.

What a drag.

Right after Christmas, we flew to San Diego with our

daughter’s family, and on New Year’s Eve, we all met up with my son’s family in

Laguna Beach. Six grandchildren together. The cousins are between four and ten

and they greeted each other with wild enthusiasm … an enthusiasm that never abated

over the entire four days. Boy, I want that kind of energy again.

The warm and sunny weather made a perfect respite from the

storms lashing our homes in New York and Nebraska. My daughter’s husband went

on a Steve Dancy marathon, reading three of the four books in the series. He runs a demanding construction supply business and has difficulty

finding time to read with three kids jumping all over him when he gets home. I

was flattered he enjoyed the books, and glad he could relax with some of my

best friends.

|

| Honest westerns ... filled with dishonest characters. |

I had a reading marathon of my own. I rediscovered a

favorite author. I read two Stephen Hunter novels and started a third. It had been over a decade since I had read one of his books, and I had

forgotten he was an exceptional storyteller and gifted writer. It’s rare nowadays

for authors to keep doing top notch work once they have scaled the bestseller

lists. When millions of dollars are at stake, deadlines become brutal. Stephen

Hunter is an exception. His latest book, The Third Bullet is as well written as his first Bob Lee Swagger novel.

One of my great joys in life used to be reading novels. Since

I started writing fiction, I have become so critical it interferes with the

pleasure of reading. Instead of being emerged in the story, I keep seeing plot

holes, meandering points-of-view, outright errors, sloppy research, and lazy

writing. This is not the case with Stephen Hunter books. He writes with a no-nonsense

style, moves his stories forward with a sure hand, and polishes the narrative to an impeccable

shine. As a Pulitzer Prize winning movie critic, he was required to have a firm

understanding of characterization, plot, and pacing. Oh yeah, he also had to

know how to write good prose lickety-split.

So, while you wait for the next Steve Dancy Tale, try a Bob Lee Swagger tale. (You can start anywhere since Hunter does a good job of

making each book self-contained.)

Monday, December 9, 2013

A Writing Cheat Sheet

Many seem to believe if they just got a proper set of instructions,

they could be a good writer. Many famous writers like Mark Twain, George

Orwell, and Elmore Leonard have even provided aspiring writers a list of rules. Here is a Writing Tips PDF that collects rules

from George Orwell, Edward Tufte, Strunk and White’s, and Robert Heinlein. I

especially enjoyed Evil Metaphors and Phrases. These clichés are definitely cringe

worthy, if I can be allowed to use yet another cliché.

(Here is my collection of writing advice.)

(Here is my collection of writing advice.)

There's a problem with all of these lists. If hard

rules were all that was necessary to become a great writer, then we’d be awash

in breathtaking literature. We have

writing tips, rules, and guidelines aplenty, yet they don’t seem to convey the

masters’ magic. What gives? All of the rules are good writing advice, but first there must be compelling content.

I used to golf

until I realized I pretended to enjoy the game. Prior to making this

discovery, I took a lesson with two friends from a teaching pro. We spent about

two hours on the range and putting green. Lots and lots of tips and advice. My

head was swimming. I couldn’t get my grip right for fear my backswing was too

fast.

The all-day lesson included a round of golf with the teaching pro. We

presumed he would critique our play as we went along. No way.

On the first tee, he told us he wouldn’t comment on our play until we were ensconced in the clubhouse for refreshments. He said we should forget everything he had told us. Forget it all. His advice was meant for the driving range and putting green. He reiterated that as we played this round, we were not to worry

about grip, swing, or stance. We should concentrate on one thing and one thing

only—keep our eye on the

ball. Simple. Keep focused on the primary basic of all the basics. It was a fun round

of golf with one of my lowest scores.

My point is that when you write a first draft, forget the

rules. Focus solely on the story. Telling a great story is the real magic the masters have mastered. Don’t pull out the rules until

you start the second draft, then use them ruthlessly on the third and fourth draft. Hone and polish your manuscript until it’s as bright and shiny

as a new penny. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist

closing with an “Evil Metaphor.”)

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Banned authors clobber the banners!

I was unaware that my favorite library once banned a book by

my favorite author. In 1885, the Concord Free Public Library banned The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark

Twain. You should never slight Mark Twain. He responded immediately to the

ban by declaring:

I was unaware that my favorite library once banned a book by

my favorite author. In 1885, the Concord Free Public Library banned The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark

Twain. You should never slight Mark Twain. He responded immediately to the

ban by declaring:“Apparently, the Concord library has condemned Huck as ‘trash and only suitable for the slums.’ This will sell us another twenty-five thousand copies for sure!”

Too bad Twain is not around to chasten those who still want

to condemn Huck. Nowadays, they want

to ban the book for using the n-word. Ironic, since his intent was to expose

and ridicule racism.

Flavorwire has published 10 Famous

Authors’ Funniest Responses to Their Books Being Banned. The moral of the

story is to never attack someone who knows how to wield a keyboard. My

favorite is Ray Bradbury’s reponse.

“… it is a mad world and it will get madder if we allow the minorities, be they dwarf or giant, orangutan or dolphin, nuclear-head or water-conversationalist, pro-computerologist or Neo-Luddite, simpleton or sage, to interfere with aesthetics. The real world is the playing ground for each and every group, to make or unmake laws. But the tip of the nose of my book or stories or poems is where their rights and my territorial imperatives begin, run and rule. If Mormons do not like my plays, let them write their own. If the Irish hate my Dublin stories, let them rent typewriters. If teachers and grammar school editors find my jawbreaker sentences shatter their mushmild teeth, let them eat stale cake dunked in weak tea of their own ungodly manufacture. ”

Monday, October 28, 2013

I'm not one of them!

Some people are visual. I'm not one of them. But I appreciate good design, even if I'm incapable of drawing a straight line with a ruler. In school, I took drawing and drafting. I received a dubious C in both. (I did better in English and history.)

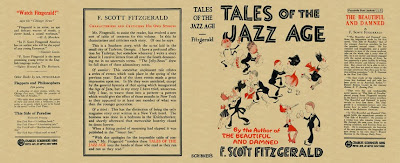

Writing and design come together in book covers. Every book, even an e-book needs a cover. And people really do judge a book by its cover. (See Judging a Book by its cover.) I'm always interested in cover design because book covers are so key to book sales. Flavorwire has done a fun piece on 75 Vintage Dust Jackets of Classic Books. Here are a few examples that struck my untutored eye.

Writing and design come together in book covers. Every book, even an e-book needs a cover. And people really do judge a book by its cover. (See Judging a Book by its cover.) I'm always interested in cover design because book covers are so key to book sales. Flavorwire has done a fun piece on 75 Vintage Dust Jackets of Classic Books. Here are a few examples that struck my untutored eye.

Not included in the Flavorwire article, but still one of my favorites.

Related Posts

Monday, October 21, 2013

The complex lives of common people

Shane is one of my favorite Western films. The Jack Schaefer book is also one of my favorite Western novels. There are great films and there are

great books, but Shane is a rare instance where both the book and film are distinguished in their own right. The movie is an honest rendition of Schaefer’s story, while

artfully making adjustments for a visual presentation of a novel.

In honor of its 60th anniversary, Andre

Soares wrote a Alt Film Guide piece about the movie. I didn’t like the article. Among other things, Soares seems apologetic

that he admires the film. After all, this is an art film site, and how could a

Western be art? The following paragraph reveals his prejudice.

“Now, what makes Shane special is that while Stevens and Gurthrie Jr.’s movie feels like a paean to the Old West and to Western movies in general, it actually demythologizes both American history and the film genre that turned into stars the likes of Tom Mix, John Wayne, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and, later on, Clint Eastwood. Read between the lines and you’ll see how subversive Shane is — how unheroic its heroes are, how complex the lives and minds of its "common people," how civilization can be just another manifestation of barbarism; and, no matter their righteousness, how hollow human victories can be.”

What claptrap. This is basically a glass-half-empty view of

humankind. The film I saw was far more uplifting and hopeful. Shane is a story of redemption, not the barbarism of civilization. To justify his

admiration for Shane, Soares basically claims there is a depth to the story

that is uncharacteristic of the genre. He needs to read and watch more Westerns. Sure, there

are lots of junky Westerns, but despite Raymond Chandler writing great fiction,

a lot of crime drama is also unmemorable. The depth and nuance of Schaefer’s

story is not uncommon, nor are instances of quality in Westerns any more rare

than for other popular genres.

Shane is a great story, presented admirably in the print and film versions. Just ask Clint Eastwood and Robert Day, the directors of Pale Rider and The Quick and the Dead, both basically remakes of Shane.

Friday, October 18, 2013

Mark Twain Tells Us How to Write

Mark Twain

didn't like James Fenimore Cooper’s writing. Wait, that was far too mild of a sentence. In

his article “Fenimore

Cooper's Literary Offenses,” Twain ridicules, lacerates, and skewers Cooper.

Here’s a

small sample:

Cooper's art has some defects. In one place in "Deerslayer," and in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record. There are nineteen rules governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction -- some say twenty-two. In "Deerslayer," Cooper violated eighteen of them.

This 1895 article

made me laugh out loud, but besides humor, I saw something else in the article.

If all of the criticisms of Cooper were rewritten as positive statements, they would

make a great guide to great writing. I believe this list can stand prominently

next to Elmore

Leonard’s Ten Rules of Writing.

So … with clemency

from Twain, I present the "18 Commandments of Writing," by Mark Twain.

- A tale shall accomplish something and arrive somewhere.

- Episodes in a tale shall be necessary parts of the tale, and shall help to develop it.

- Personages in a tale shall be alive, except in the case of corpses, and that always the reader shall be able to tell the corpses from the others.

- Personages in a tale, both dead and alive, shall exhibit a sufficient excuse for being there.

- When the personages of a tale deal in conversation, the talk shall sound like human talk, and be talk such as human beings would be likely to talk in the given circumstances, and have a discoverable meaning, also a discoverable purpose, and a show of relevancy, and remain in the neighborhood of the subject at hand, and be interesting to the reader, and help out the tale, and stop when the people cannot think of anything more to say.

- When the author describes the character of a personage in the tale, the conduct and conversation of that personage shall justify said description.

- When a personage talks like an illustrated, gilt-edged, tree-calf, hand-tooled, seven- dollar Friendship's Offering in the beginning of a paragraph, he shall not talk like a Negro minstrel in the end of it.

- Crass stupidities shall not be played upon the reader by either the author or the people in the tale.

- Personages of a tale shall confine themselves to possibilities and let miracles alone; or, if they venture a miracle, the author must so plausibly set it forth as to make it look possible and reasonable.

- The author shall make the reader feel a deep interest in the personages of his tale and in their fate; and that he shall make the reader love the good people in the tale and hate the bad ones.

- Characters in a tale shall be so clearly defined that the reader can tell beforehand what each will do in a given emergency.

- Say what he is proposing to say, not merely come near it.

- Use the right word, not its second cousin.

- Eschew surplusage.

- Do not omit necessary details.

- Avoid slovenliness of form.

- Use good grammar.

- Employ a simple and straightforward style.

Great list,

huh? Anyway, I’ll let Twain conclude this post with his conclusions about Cooper:

I may be mistaken, but it does seem to me that "Deerslayer" is not a work of art in any sense; it does seem to me that it is destitute of every detail that goes to the making of a work of art; in truth, it seems to me that "Deerslayer" is just simply a literary delirium tremens. A work of art? It has no invention; it has no order, system, sequence, or result; it has no lifelikeness, no thrill, no stir, no seeming of reality; its characters are confusedly drawn, and by their acts and words they prove that they are not the sort of people the author claims that they are; its humor is pathetic; its pathos is funny; its conversations are -- oh! Indescribable; its love-scenes odious; its English a crime against the language.

Counting these out, what is left is Art. I think we must all admit that.

Remind me

never to get on the bad side of Twain.

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Book Review: Truman by David McCullough

Harry Truman

is an interesting character, and David McCullough presents an engaging picture of

our 33rd president. McCullough is thorough and readable as he presents

a chronological narrative of Truman’s life. Although a credentialed historian,

McCullough avoids academic gobbledygook and knows when to end a sentence. He

writes in a clean, straightforward fashion that invites the reader to turn the

page.

When

McCullough writes a biography, he investigates every nook and cranny of the

subject’s life until he knows everything knowable about the individual. Attention

to detail reveals the real person behind the public facade, but this fixation

on the subject produces two flaws in McCullough books: they’re too

long and the supporting cast are often cardboard cutouts.

At 1,120

pages, Truman is a long book. A very long book. After gathering all this

information, McCullough doesn't know what to leave out. The 1948 presidential

race was historic, but after dozens of pages, I came to believe we would

witness every whistle-stop. This is just one example of overwhelming detail. Truman would have remained a tome if

cut by 200 pages, but the book would have been a more powerful biography.

McCullough’s

focus on the subject of his biographies gives slight notice to other prominent

people. The collection of great or notorious leaders during the World War II

period probably rivaled the Revolution. At these rare times in history,

collective greatness molds and/or reinforces the accomplishments of each

individual player. (Doris Kearns Goodwin is a master at capturing the dynamics

and undercurrents of formidable characters at formidable moments.) We learn

everything about the character and actions of Truman, but Franklin D.

Roosevelt, George C. Marshall, Winston Churchill, Dwight Eisenhower, and the

members of his cabinet and staff rotate around Truman with all the animation of

carousel ponies. We have faint idea what Roosevelt thought about Truman or why

he picked him to be vice president and then chose to ignore him after the

election. FDR knew his health was failing, and handpicked a relatively obscure

junior senator as his successor. Why? McCullough does not give us much insight

because we see events only from Truman’s perspective.

Truman was an enjoyable read and a highly professional biography of one of our best presidents. Despite my grumblings, I read every word of this fine book and returned to reading it at every opportunity. I would highly recommend it … supplemented with other history books about this pivotal period in our history.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

The art of the short story has always eluded me

Western

author JR Sanders posted to Facebook a link to “The

Top 20 Literary Quotes About Short Stories,” at Writers Write, a South African website. (It was posted

yesterday. Ain’t modern technology grand?) My favorite quote was from David Sedaris,

“A good [short story] would take me out of myself and then stuff me back in,

outsized, now, and uneasy with the fit.”

The article

reminded me that I have never done well with the short form of storytelling.

I love to

read short stories and own many collections, but I don’t have the time to write

one. My last comment, of course is not a new thought. Pascal wrote, “I have

made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.”

In 1690 the

philosopher John Locke wrote about a famous work, “But

to confess the Truth, I am now too lazy, or too busy to make it shorter.”

In 1750

Benjamin Franklin composed a letter describing his groundbreaking experiments

involving electricity, writing, “I have already made this paper too long, for

which I must crave pardon, not having now time to make it shorter.”

In 1857

Henry David Thoreau wrote in a letter to a friend that “Not that the story need

be long, but it will take a long while to make it short.”

Woodrow

Wilson was asked by a member of his cabinet about the amount of time he spent

preparing speeches. He said, “It depends. If I am to speak ten minutes, I need

a week for preparation; if fifteen minutes, three days; if half an hour, two

days; if an hour, I am ready now.”

(Credit for

the above quotations goes to Quote

Investigator, a good site for writers.)

Abraham

Lincoln spent untold hours crafting the Gettysburg Address, which at 271 words

is one of the shortest and most famed political speeches of all time.

Brevity done

with forethought is powerful. A comedian’s quip can destroy a longwinded speech.

Just ask any target of Will Roger’s wit.

Ever since the demise of the family weekly magazine, short fiction has had few outlets. This is a shame. Western Writers of America occasionally publishes an anthology of short Western works, but there are few other places to even submit short stories.

Perhaps Amazon will once again redefine the market. The online bookseller has started Kindle Singles, which are short works in both fiction and nonfiction. The idea seems to be catching on because many national bestselling authors are publishing short works in this manner. Although I don't write short stories, I hope Kindle Singles revives the form. After all, throughout history, art has needed powerful sponsors.

Perhaps Amazon will once again redefine the market. The online bookseller has started Kindle Singles, which are short works in both fiction and nonfiction. The idea seems to be catching on because many national bestselling authors are publishing short works in this manner. Although I don't write short stories, I hope Kindle Singles revives the form. After all, throughout history, art has needed powerful sponsors.

Thursday, October 3, 2013

Indie Publishing Rewrites Promotion

Kim McDougall of Castelane, Inc. recently wrote to ask for permission to re-publish on the new Castlelane website an article I wrote for Turning Point . I agreed, but in rereading the article, I decided it could use an update. Here is the revised article.

There’s not much you can believe about indie-publishing. Information from indie-publishing houses is

suspect, and most of the other data comes from people who make their living off

striving writers. As someone who has

published with a traditional house and indie-published, I’ll try to give you

the straight scoop.

First, I Indie-publish by choice. It didn't start out that way, but now I’m

convinced that indie-publishing is the best route for me.

My first book was published by Wiley. It was an agented, non-fiction book. After I completed my first novel, Tempest at Dawn, I secured a different

New York agent that specialized in fiction.

While the agent shopped my lengthy, historical novel, I wrote a genre

Western titled The Shopkeeper. Since the typical advance for a Western

wouldn't make a decent down-payment on a Nissan Versa, my agent declined to

represent it. No problem, I’d indie-publish.

Currently, my novels are in print, large print, audio, and e-book formats. My large print and

audio contracts are traditional contracts with advances, so I still have a foot in each world. I’m

making money, but what is more important, my platform continues to grow. (My agent didn’t sell Tempest at Dawn, so I ended up indie-publishing it as well.)

Why I Stay with Indie-Publishing

That’s how I started indie-publishing, but why do I stay

with it after building a respectable platform? Three reasons: speed, income, and control.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)