Western

fiction has been hugely popular for almost two hundred years. Not only were Westerns

popular in the United States, but the whole world devoured them. For decades, the

Western was a staple of fiction, Hollywood, television, and daydreams. Today,

many think Western fiction is moribund. They’re wrong. Authors like Johnny

Boggs continue to carry on the tradition, and my own novels sell well. The

popularity of Westerns is often measured against the impossible yardstick of

the 1950s.

Some say we’ve

become too sophisticated to swallow the traditional Western mythology. Those

are people who have not taken a thoughtful look at Harry Potter, The Hunger

Games, or even the glut of superheroes that plague theaters, bookshelves,

and toy boxes. The stories are the same, only the venue has changed. The

Western in its traditional garb will come roaring back when audiences tire of

yet another iteration of CSI or men in tights.

Western

fiction is frequently dismissed as not being serious literature. This misconception

is perpetuated by classifying literary stories that occur in the Old West as

something other than a Western. Many of the smart set believe Westerns can only

be dime novels, pulp fiction, or straight-to-paperback formula bunkum. But the

Western has a long and valid history in literature.

James

Fenimore Cooper may have been the first Western author of note. The Last of

the Mohicans and the rest of the Leatherstocking Tales were told in the

Western tradition. Written in 1826 about events that supposedly occurred nearly

seventy-five years prior, The Last of the Mohicans incorporates all the

characteristics of a modern Western.

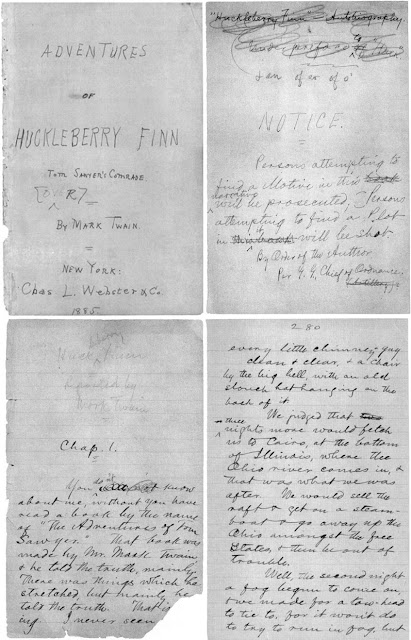

Mark Twain

is universally acknowledged as one of the great American literary figures, but

is seldom referred to as a Western writer. Yet, Roughing It is a

first-hand description of the Wild West of Virginia City during the heyday of

the Comstock Lode. Granted, Roughing It is Twain-enriched non-fiction,

but The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry

Finn are coming-of-age novels set in the American frontier. (By the way,

Mark Twain hated James Fenimore Cooper's writing. You can read all about it here. Pretty funny.)

When Owen

Wister published The Virginian in 1902, the novel received critical

acclaim and was a huge bestseller, eventually spawning five films, a successful

play, and a television series. An instant success, it sold over 20 thousand

copies in the first month, an astonishing number for the time. It went on to

sell over 200,000 thousand copies in the first year, and over a million and a

half copies prior to Wister's death. This classic has never been out of print.

Max Brand,

Zane Grey, Louis L’Amour, Jack Schaefer, Elmer Kelton, Larry McMurtry, and

Cormac McCarthy continued the Western tradition and all of them have been

highly successful. Recently Nancy E. Turner (These is my Words) and Patrick

deWitt (The Sisters Brothers) have penned praiseworthy Westerns that are

popular with readers.

Western

literature has a grand heritage and will continue to appeal to readers all over

the world. Good writing, plots that

move with assurance, and great characterization will elevate the genre back the

top of the bestseller charts.

|

| Honest westerns filled with dishonest characters. |