In novels, a story arc usually refers to rhythm of a story from introduction, to big trouble, to resolution. Basically, the rise and fall of tension and emotion in a story. In most novels, this story arc is self-contained in a single book. Not so, for television.

How does a story arc work different for television? Dictionary.com defines it as "a continuing storyline in a television series that gradually unfolds over several episodes." I would add "or seasons." Think about the hunt for Red John in the Mentalist, or the quest for the throne in Game of Thrones, or the feud between Deputy Raylan Givens and Boyd Crowder in Justified. In television, a good story arc threads it's way through multiple episodes that tell self-contained stories with a beginning, middle, and end.

Despite the pervasiveness of the term, everything carried along from one episode to another is not a story arc. "Space: the final frontier" from Star Trek is setting, not story arc. The solution of the crime in Bosch takes an entire season, but this television program is more akin to what we used to call a mini-series. Same for the old television program 24. These are dramatizations of a novel or single story over many episodes. A true story arc involves an embedded, larger mystery in a series of smaller stories. Without closure to this grand mystery, the series is hard to put aside. It's also important that a story arc can be resolved. In fact, it is the promise of resolution that draws in the audience week after week. They want the answer to this puzzle.

So, can the television style of a story arc help pull along readers of a book series? I'm not an expert, but J. K. Rowling is. Each Harry Potter included a self-contained story, along with the gradual reveal of the Lord Voldemort mystery. Handled deftly, a long running story arc can pull readers through the entire series. The problem is you can't string along readers forever. Readers feel they are owed resolution. The trick is to present this resolution in a manner that is not the death knell of the story.

Crossing the Animas resolves the series-long story arc of the Steve Dancy Tales. It's yet to be seen if I did it in a manner that allows me to reboot the series with a wholly new story arc.

I bet I did. Just wait. See where the story goes next.

Showing posts with label #WritingTips. Show all posts

Showing posts with label #WritingTips. Show all posts

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Monday, November 30, 2015

Literature vs. Popular Fiction

I bounce around the internet each

morning after checking email. I scan a lot of articles, but rarely get by the

first few paragraphs. My time is precious and there is just so much stuff out

there. If I tried to read it all, I’d never have time to write.

An exception was “Literature vs genre is a battle where both sides lose” by David Mitchell, published at The Guardian

blog. I don’t enjoy dissertations on writing as an art form. I’m a storyteller

whose medium is the written word, so I prefer articles about how to improve my

craft. But Mitchell grabbed my attention with his first sentence.

“Literary fiction is an artificial

luxury brand but it doesn’t sell.”

There is an audience for literary

fiction, but Mitchell points out that the demand for genre fiction dwarfs the high-tone

variety. He claims, “fancy reading habits don’t make you cool any longer. The

people who actually buy books, in thumpingly large numbers, are genre readers.”

I think the difference is how a

writer approaches a project. If a writer starts off to tell a story, a good craftsman will focus on writing the novel properly to keep the reader

engaged. If a writer starts with the goal to write a literary masterpiece,

then the focus becomes assembling sentences so clever they stop the reader to admire

the prose. A good storyteller never takes the reader out of a story, so fancy

writing is counterproductive.

Here’s the dirty little secret of

fiction writing: if it doesn’t sell, it’s soon forgotten. Mark Twain,

Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Owen Wister, Raymond Chandler, Louisa May Alcott and

many other “Great Writers” understood this truism.

“It might reasonably be said that all art at some time and in some manner becomes mass entertainment, and that if it does not it dies and is forgotten.” Raymond Chandler

|

| Honest westerns filled with dishonest characters |

Monday, September 14, 2015

John Steinbeck Writing Tips

Six tips on writing from Pulitzer Prize winner and Nobel

laureate John Steinbeck.

- Abandon the idea that you are ever going to finish. Lose track of the 400 pages and write just one page for each day, it helps. Then when it gets finished, you are always surprised.

- Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material.

- Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader. I have found that sometimes it helps to pick out one person—a real person you know, or an imagined person and write to that one.

- If a scene or a section gets the better of you and you still think you want it—bypass it and go on. When you have finished the whole you can come back to it and then you may find that the reason it gave trouble is because it didn’t belong there.

- Beware of a scene that becomes too dear to you, dearer than the rest. It will usually be found that it is out of drawing.

- If you are using dialogue—say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.

Sunday, August 9, 2015

Henry Miller's Commandments

|

| Henry Miller, circa 1930 |

|

| Planes, Trains, and Automobiles |

Die-hard Miller fans will say he had a point, but it's something along the lines of "all the world is crazy except me." Only the first part of that phrase may be true, and I expressed the point in five words.

My opinion of Miller might be biased because I think he was a jerk. Miller constantly harangued friends and acquaintances to supply his needs, and then heaped scorn on them if they complied. (This was especially true for women.) In his view, a worthy human would never kowtow to his entreaties. Much like Grocho, he didn’t want, “to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members.”

My opinion of Miller might be biased because I think he was a jerk. Miller constantly harangued friends and acquaintances to supply his needs, and then heaped scorn on them if they complied. (This was especially true for women.) In his view, a worthy human would never kowtow to his entreaties. Much like Grocho, he didn’t want, “to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members.”

Despite my reservations, I’ll include his writing advice

because many believe that Henry Miller was a literary giant. In typical Miller

fashion, he called these commandments.

- Work on one thing at a time until finished.

- Don’t be nervous. Work calmly, joyously, recklessly on whatever is in hand.

- Work according to Program and not according to mood. Stop at the appointed time!

- When you can’t create you can work.

- Cement a little every day, rather than add new fertilizers.

- Keep human! See people, go places, drink if you feel like it.

- Don’t be a draught-horse! Work with pleasure only.

- Discard the Program when you feel like it—but go back to it next day. Concentrate. Narrow down. Exclude.

- Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing.

- Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.

Monday, July 20, 2015

Writing Tips from Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway never published advice for aspiring writers,

but he spoke or wrote enough about writing that Larry W. Phillips was able to

edit a collection of his reflections on the craft. (Ernest Hemingway on Writing)

In the preface, Phillips writes, “Throughout

Hemingway’s career as a writer, he maintained that it was bad luck to talk

about writing—that it takes off ‘whatever butterflies have on their wings and

the arrangement of hawk’s feathers if you show it or talk about it.’ Despite

this belief, by the end of his life he had done just what he intended not to

do. In his novels and stories, in letters to editors, friends, fellow artists,

and critics, in interviews and in commissioned articles on the subject,

Hemingway wrote often about writing.”

Here’s one piece of advice I like:

Hemingway said to F. Scott Fitzgerald that, “I

write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of shit. I try to put the

shit in the wastebasket.”

This nugget reminds me of a photography course I took

many years ago with my wife. (She got an A while I received only a B. Darn. And

we took pictures of the same subjects.) Anyway, the teacher told us if we

wanted to build a reputation as good photographer, we should take lots and lots of

pictures and throw all of the bad ones away. Simple … but expensive in the age

of film photography. In the digital age, this advice has become cost free. If

adhered to religiously, this technique allows a visual dufus like me to catch

up with my wife.

Here are some more tips gleaned from Hemingway lifelong

musings about writing.

- Use short sentences.

- Use short first paragraphs.

- Use vigorous English.

- Be positive, not negative.

- To get started, write one true sentence.

- Always stop for the day while you still know what will happen next.

- Never think about the story when you’re not working.

- Don’t describe an emotion–make it.

- Be Brief.

- The first draft of everything is shit.

- Prose is architecture, not interior decoration.

- Write drunk, edit sober.

If you’re inclined, there’s even an app that will measure your writing clarity against Hemingway. I’m not one for machine

assisted writing tools, but at $9.99, this one seems inexpensive. I bought it

and tried it out on this post. It received a “good” score. Ironically, the quote from Larry W. Phillips was highlighted as the least comprehensible.

Friday, July 10, 2015

Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling

Scripts guidelines help storytelling. First Loony Tunes, now Pixar. The animated world has rules. Perhaps it's related to Walt Disney's comment that he liked animated features because he could control everything. He didn't need to deal with unruly actors.

Here are Pixar's 22 Rules. Way more than Roadrunner's 9 or Bonanza's 7.

Here are Pixar's 22 Rules. Way more than Roadrunner's 9 or Bonanza's 7.

#1: You admire a character for trying more than for their successes.

#2: You gotta keep in mind what’s interesting to you as an audience, not what’s fun to do as a writer. They can be v. different.

#3: Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

#4: Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

#5: Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff but it sets you free.

#6: What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

#7: Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.

#8: Finish your story, let go even if it’s not perfect. In an ideal world you have both, but move on. Do better next time.

#9: When you’re stuck, make a list of what WOULDN’T happen next. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up.

#10: Pull apart the stories you like. What you like in them is a part of you; you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it.

#11: Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

#12: Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th – get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

#13: Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.

#14: Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

#15: If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

#16: What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

#17: No work is ever wasted. If it’s not working, let go and move on – it’ll come back around to be useful later.

#18: You have to know yourself: the difference between doing your best & fussing. Story is testing, not refining.

#19: Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.

#20: Exercise: take the building blocks of a movie you dislike. How d’you rearrange them into what you DO like?

#21: You gotta identify with your situation/characters, can’t just write ‘cool’. What would make YOU act that way?

#22: What’s the essence of your story? Most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build out from there.

|

| Click to see Pixar's 23 Years |

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

Characters Matter

Characterization

is a crucial aspect of fiction. We know this because it's drilled into us at

school, in workshops, and in all the how-to books and journals we read. The

protagonist must come across as real and interesting enough to pull the reader

all the way through to the end of the story. A common mistake, however, is to

focus too much attention on the protagonist. When you read a great book or

watch an outstanding film, it's usually the antagonist that lifts the story

above the ordinary.

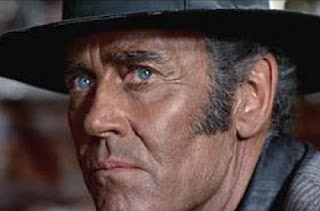

|

| A favorite villain: Frank in Once Upon a Time in the West |

Protagonists,

especially those of the heroic breed, are bound by rules and common perceptions

that somewhat inhibit creativity. Antagonists, on the other hand, are wide open

for manipulation. They can be bad to the bone like Hannibal Lector or Chigurh.

They can be nasty or evil, but mend their wayward ways like Ebenezer Scrooge or

Darth Vader. The reader may be misdirected to believe the antagonist is bad and

then everything is flipped around like with Boo Radley and Mr. Darcy.

Antagonists can make a story memorable even when they are not even human, like

Moby Dick or Christine. The one thing these antagonists all have in common is

great character development.

Concentration

on character development shouldn't stop with the protagonist and antagonist. Nobody

willingly hangs around with boring people and nobody wants to read about

characters with cornmeal personalities—not even the bit players. Everybody

inside the covers of your book has to be interesting. Give each of them a

distinct personality. If you have a character like a postman or waitress that

appears only for a couple pages, don't slow down the story by describing their

personality, show it. You need to do it with dress, movement, or dialogue.

Show, don't tell, is more difficult with the brevity of a minor player, but you

only need to spice the character enough to make him or her three dimensional.

A fictional

work has a single writer with a single personality. If you populate your work

with slight variations of yourself, you'll create a homogeneous universe that

will bore people silly. A writer must suppress their own personality when

developing characters so they are all different from each other. It's not

enough that they look and talk different—they must think and act differently.

They must be different people.

The fiction

writer's personality will show up in the total work, but it's best if it's not

directly reflected in the characters, especially the protagonist or antagonist.

Have fun with these two. Make them unique from yourself and every other

character in your work. This is especially true for the antagonist.

A really good bad guy or gal gives a hero a reason to be heroic.

A really good bad guy or gal gives a hero a reason to be heroic.

Monday, June 22, 2015

9 Golden rules for the Road Runner and Coyote

Chuck Jones created 9 Golden rules for the Road Runner cartoons. These famous rules insured that fans received exactly what they expected from these Loony Tunes characters. First the rules, and then some storytelling lessons we can draw from this popular series.

Rule 1. The Road Runner cannot harm the coyote except by going “beep, beep!”

Rule 2. No outside force can harm the coyote—only his own ineptitude or the failure of the Acme products

Rule 3. The coyote can stop anytime—if he were not a fanatic. (Repeat: “A fanatic is one who redoubles his efforts when he has forgotten his aim.” George Santayana)

Rule 4. No dialogue ever, except “Beep Beep!”

Rule 5. The Road Runner must stay on the road—otherwise logically he would not be called Road Runner.

Rule 6. All action must be confined to the natural environment of the two characters—the Southwest American desert.

Rule 7. All material, tools, weapons, or mechanical conveniences must be obtained from the Acme Corporation.

Rule 8. Whenever possible, make gravity the coyote’s greatest enemy.

Rule 9. The coyote is always more humiliated than harmed by his failures.

|

| Chuck's handwritten rules |

Previously,

I published the 7 rules for

the television series Bonanza. Television series, movie franchises, and even

cartoons need a list of dos and don’ts so the characters and action remain consistency from

episode to episode. Book series need the same. The protagonist must remain true

to his or her character and the plot cannot go too far afield without losing

fans. If you write a series, or even a single novel, write down the plot and

character rules. This little exercise brings clarity and dependability to stories.

There

are additional lessons to be gleaned from the Road Runner and Coyote. All stories revolve around an antagonist making life difficult for the protagonist. Different stories can have a multiple number of one or the other. Although Steve Dancy is the main

protagonist in my Western novels, he has two (and now three) characters in secondary

protagonist roles. Multiple bad guys or gals are also not uncommon.

After these main

characters, the entire story is usually populated with all sorts of supporting and bit players. What

if we were to whittle this down to the bare essentials? Could a story be told in a world populated by only one protagonist relentlessly pursued by a single

antagonist? Steven Spielberg’s first movie Duel meets this criteria, as well as Tom Hanks’ Cast Away. These are intimate, tense stories. Of course, the Road Runner

cartoons fits this minimalist construct. In fact, the Road Runner has no

dialogue except for a single word repeated twice.

After these main

characters, the entire story is usually populated with all sorts of supporting and bit players. What

if we were to whittle this down to the bare essentials? Could a story be told in a world populated by only one protagonist relentlessly pursued by a single

antagonist? Steven Spielberg’s first movie Duel meets this criteria, as well as Tom Hanks’ Cast Away. These are intimate, tense stories. Of course, the Road Runner

cartoons fits this minimalist construct. In fact, the Road Runner has no

dialogue except for a single word repeated twice.

How

in the world can you keep audience interest with these limitations? Watch. You’ll

see storytelling reduced to its barest elements. Even if you have a cast of

thousands, you can keep the reader’s interest by following the precepts

displayed so eloquently by Road Runner cartoons.

Sunday, June 14, 2015

People Love That Story

|

| Kurt Vonnegut |

I'm collecting writing tips from famous author's. You can read them here. In this post, I'm adding Kurt Vonnegut’s writing tips. Good advice from an expert storyteller.

Although I posted it before, I also wanted to share his amusing description of story forms. Behind the entertaining presentation, Kurt presents some solid analysis of the art of storytelling. So if you want to hear it from the horses mouth, watch the video below.

Here are Kurt Vonnegut’s "8 Tips on How to Write a Great Story."

- Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

- Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

- Every sentence must do one of two things — reveal character or advance the action.

- Start as close to the end as possible.

- Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them-in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

- Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

- Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

Monday, March 30, 2015

How to become an overnight success!

|

| Fame is but 70,000 words away |

Recently I

talked with an aspiring writer who felt unsure about her first novel. She asked

how I started. Specifically, she wanted to know if I tried nonfiction, short

pieces, or just jumped directly into a novel. She wanted to know if I had help.

Did I take classes, use a writing coach, or read books about the craft of

writing. The questions came in a torrent. My response, a single syllable.

“Yes.”

I always

wanted to be a novelist. In fact, I started college as an English major. I

could tell a good story, but my grammar and spelling embarrassed me so often, I switched to economics. I never again thought about writing until I

had a brilliant idea for a novel. That idea started me on an extended foray into

abject disillusionment and rejection. After shoe boxes full of rejections, an agent took the time to tell

me that my book was crap, although he did give me credit for an intriguing storyline. The bottom of his short note read, “Writing is a

profession, leave it to people who know what they’re doing.”

No more

writing for years.

Then an

interesting event took place. A professional journal approached me for an

article about a technology success I had managed as CIO for a major

corporation. That’s when I discovered editors. My piece laid out our technical project

as a story about overcoming challenges, but my spelling and grammar—after all these years—still needed help. The editor not

only fixed my flaws, but showed me every change she had made. I went through

each and every one trying to learn how to do a better job next time. There were

seven more “next times,” and each journal article improved until I felt I was

getting the hang of writing.

Next, I

started writing magazine articles. These were still nonfiction, technical pieces,

but I branched away from computers to write about other subjects. But not

for long. In a fit of optimism, I put together a proposal for a nonfiction book about

managing computer professionals.

There’s an

old saying in publishing that nonfiction depends on credentials and fiction

depends on platform. Like a lot of clichés, this one has some truth to it.

Because of my title as CTO of a Fortune 50 company, my book acquired an agent

and publisher lickety-split. This endeavor became The Digital Organization, published by Wiley &Sons. The

entire experience was a nightmare. Now, I discovered a new kind of editor—not

one who fixed my transgressions, but one with the power to dictate content. The

process was glacial. Not a good attribute for a book about the speed-of-light

computer industry. I vowed never again to invest so much time on a book with a

shelf-life measured in nano-seconds.

After a few

failed nonfiction proposals, I wanted to try my hand at fiction again.

I started by reading books that promised to teach the craft of novel writing. Definitely

a mixed bag. After I got five chapters of my novel as close to perfect as

possible, I hired a writing coach from Gotham Writers' Workshop. I discovered I had underestimated

perfect. Despite a manuscript spattered with red ink, the coach was highly

encouraging. She believed my book had serious potential and gave me numerous

tips on how to get it to a professional level. Upon finishing Tempest at Dawn, I easily acquired an

agent with McIntosh & Otis. I was going to be famous.

Not so much.

The agent shopped the book around and received enough positive feedback to keep

the effort up for a couple of years, but in the end, everyone decided to “pass”

on my novel about the Constitutional Convention. In the meantime, I wrote a

western titled The Shopkeeper, and a

series was born.

I have now written nine novels, two nonfiction books, and ghostwritten books for celebrities. All of them have done respectable, but it was the Steve Dancy character who caught readers’ attention. The enthusiasm for the series surprised me, especially among women readers. I thought Westerns were dead. Instead, I discovered an eager audience for traditional heroes who dispatch bad men.

I have now written nine novels, two nonfiction books, and ghostwritten books for celebrities. All of them have done respectable, but it was the Steve Dancy character who caught readers’ attention. The enthusiasm for the series surprised me, especially among women readers. I thought Westerns were dead. Instead, I discovered an eager audience for traditional heroes who dispatch bad men.

And the best part: Westerns have a looong shelf life. Just ask Louis L’Amour.

|

| Honest stories filled with dishonest characters. |

Monday, March 9, 2015

Cover Up!

We finally decided

on a cover for Jenny’s Revenge, A Steve Dancy Tale. During the course of

our selection, I found an interesting article titled: What Makes for a Brilliant Book Cover? A Master Explains. The master is Peter Mendelsund, who

designed the book cover for The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo among many other

titles. (You can see some of the rejected Girl covers by following the link.)

Here are quotes I

like from the article:

Spine Most Important “On one level, dust jackets are billboards. They’re meant to lure in potential readers.”

“A truly great jacket is one that captures the book inside it in some fundamental and perhaps unforeseen way.”“If this author got a big advance, then you’re going to have to jump through some flaming hoops.”

“The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: It had to have what designers refer to as ‘the Big Book Look.’ In other words: really, really big text … Mendelsund did what he describes as the ‘dumbass thing’ of echoing the title visually on the cover itself, putting the text on top of an image of… a dragon tattoo. It was the rare case in which a novel had so much momentum that the best thing a designer could do was stay out of the way … The design featured at least one small victory against the obvious: the bright yellow backdrop … ‘Up until that point, I would defy you to find a dark gothic thriller with a day-glow cover,’ he says.”

I’ve written a number of articles about book cover because they're important. People really do judge a book by its cover. Something to keep in mind, however, is that until an author breaks into the NYT Bestseller List, the spine is the most important part of the design because that's all anyone will see on the shelf of a brick and mortar bookstore.

|

| Honest Westerns ... filled with dishonest characters |

When we selected the

cover for the first Steve Dancy Tale, we used an L. A. Huffman Montana

Territory portrait from around 1880. Most genre Westerns displayed an illustrated action

cover in eye-catching colors. We went with black and white photography to

signal that The Shopkeeper was a different kind of Western. We've stuck with

black and white period photography ever since.

The designer is my

son by the way. I’m getting back his tuition from that pricey art school one

book cover at a time. When we did the

cover for The Return, the fourth book in the series, I asked if my name could

be larger. He informed me that when my name became bigger than the title, I’d

be toast.

Monday, February 16, 2015

To Each His Own

Some author’s

dread poor reviews from readers. I like to hear what readers think and find I learn

more from critical reviews. Besides, what some readers find objectionable, other readers enjoy. I never had a better example than today when I received two Amazon

reviews that had exactly opposite takes on a major plot element of The Return.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Marilyn says, "Not as good the previous books in the series. Get Steve Dancy back to the West where he seems at home."

While another Amazon Customer wrote, "Enjoyed the Western theme, along with the Edison involvement. New York gangs added flavor that made this a great read."

No author can please every reader and it's career suicide to try. Don't ignore poor reviews because they can help you become a better writer, but keep your focus on the total weight of all of your reviews. Every writer will get a few bad reviews, so take them with a grain of salt.

Wednesday, February 4, 2015

Too much information

Speed bumps take readers out of the story.

The final throes of revising Jenny’s Revenge reminded me that too much information doesn't help a story. Nothing bores a reader more than needless explanations about trivial matters the reader can fill in for themselves. Pointless factoids, excessive description, and extraneous words make an otherwise good novel clunky and laborious.

This old lesson has special application to my writing

because I have a need to neatly tie up every little thing. My brain somehow requires an explanation for every action by every character. This is important for the main plot,

but can be distracting when it comes to tributaries. In fact, some tributaries can turn the plotline into a muddy mess. I also have a habit of

siring orphans. In an initial draft, I'll launch a subplot, never to return to it. Most readers may not remember the distraction, but the dead end will irritate those that do. More often than not, I find a simple solution: send the orphan to the bit bucket.

My goal during revision is to cut everything that doesn’t

move the story forward. Goals aren’t always achieved, so it helps to have

trusted critics that will give you honest feedback. Revision is not an event,

but a process that encompasses several iterations.

This is why I believe good novels are not written, they’re

rewritten.

Monday, November 3, 2014

Expert Advice, Anyone?

In a Barnes & Noble Book Blog, Stephen King presents 20

writing tips. Most famous writers offer ten or perhaps a dozen tips, but as you may have

noticed, King is prolific. I like Stephen King, and he’s a great

storyteller. His memoir, On Writing: A

Memoir of the Craft contains a wealth of wisdom about writing. This list is

much shorter, but all writers can benefit from following his guidelines.

That said, I would quibble with a couple of his points.

First, #10 is too strict. King can write a first draft in less than three months, but

mortals need more time—especially

those who have to pay the mortgage, put food on the table, and run a couple

errands each day. Don’t hurry yourself … but never stop for an extended period.

It’s too easy to put off writing one more day when you've been on a long hiatus.

Until you make a living by writing, I disagree with #13. Few

of us have the luxury of erecting a force field around us when we write. Learn

to write with distractions … otherwise you may never complete an entire novel.

Looking for the perfect writing environment is a sure route to writers-block.

Last, #19 is balderdash. Just because you have driven a car for your entire

life doesn't mean you can join the NASCAR circuit and race at near 200 MPH in

bumper to bumper traffic. Maybe some can learn writing from reading fiction, but I

needed help. I read dozens of books on writing, participated in workshops, and

used a writing coach early on. I still read at least one book a year on the

craft of writing. On Writing by

Stephen King is a good place to start.

Here are King’s tip headlines. You can read his explanations

for each one at the Barnes

& Noble Book Blog.

|

| 10th Anniversary Edition |

1. First write for yourself, and then worry about the

audience.

2. Don’t use passive voice.

3. Avoid adverbs.

4. Avoid adverbs, especially after “he said” and “she said.”

5. But don’t obsess over perfect grammar.

6. The magic is in you.

7. Read, read, read.

8. Don’t worry about making other people happy.

9. Turn off the TV.

10. You have three months.

11. There are two secrets to success.

12. Write one word at a time.

13. Eliminate distraction.

14. Stick to your own style.

15. Dig.

16. Take a break.

17. Leave out the boring parts and kill your darlings.

18. The research shouldn’t overshadow the story.

19. You become a writer simply by reading and writing.

20. Writing is about getting happy.

Good advice. I especially like his comment in this interview

that a writer’s goal is “to make him/her forget, whenever possible, that he/she

is reading a story at all.”

Monday, October 13, 2014

Damn Research Anyway

I write historical novels. Most of my books are Westerns, and I strive to properly reflect the lifestyle, technology, and politics of the era. Tempest at Dawn, my big historic novel, is a dramatization of the Constitutional Convention. Even The Shut Mouth Society, my contemporary chase-thriller has strong historical content centered on Abraham Lincoln.

|

| Joseph Finder |

When I’m busy and I discover an interesting web article, I

bookmark it to read later. This morning, I read Joseph

Finder’s article Research:

A Writers Best Friend and a Writer’s Worst Enemy.

I think Finder has it just about right. He alludes to my worst habit: using research to procrastinate, but couches it far too narrowly. When I’m on a roll, I never let research get in the way of getting the story down in black and white. On the other hand, when I don’t really want to write, I bounce around the web and tell myself I’m making progress through research. Somehow, I convince myself of this even when I’m watching the GoPro video of the week.

I think Finder has it just about right. He alludes to my worst habit: using research to procrastinate, but couches it far too narrowly. When I’m on a roll, I never let research get in the way of getting the story down in black and white. On the other hand, when I don’t really want to write, I bounce around the web and tell myself I’m making progress through research. Somehow, I convince myself of this even when I’m watching the GoPro video of the week.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on the hazards of

web-based research. I even put together a Powerpoint presentation

for a writer’s group. Today, I use the web more frequently for research. One

reason is the proliferation of primary source documents. The second reason is that reputable institutions have digitized their

content. The web has grown up. Except for odds and ends, I rarely use Wikipedia.

There are many more authoritative sources if you know how to find them.

Research can also be in the real world. For instance, I need to walk the ground of my novels. I’m not a visual person, so I take gigabytes of pictures to look at as a write descriptive prose. Walking the ground has another purpose. Every locale has a distinct feel to it. When I deplane in Phoenix or Honolulu, I know where I’m at as soon as I feel and smell the air. Some writers are geniuses when it comes to descriptive prose, but to describe ambiance, I need to experience it. Besides, this is the fun part of research. Wandering around Virginia City or Old Denver sure beats trying to verify the exact time Virgil Earp lived in Prescott, Arizona.

Friday, September 26, 2014

The Real Wild West

Previously, I wrote that Mark

Twain is my favorite Western writer. Twain actually experienced the

West at its rowdiest and Roughing

It describes his experiences with humor and a touch of the

storyteller’s art. Owen Wister is another author who experienced the real Wild West,

which gave The Virginian its authentic feel. Wells Drury’s An Editor on the Comstock Lode is yet another great source for Western lore. In fact, its organization and humorous writing makes it an indispensable

reference source for Western writers. Drury’s time as a newspaper editor in

Virginia City gave him a front row seat to the goings on in that raucous town.

His book covers:

- Everyday life in the West, including entertainment, food, and city services

- Practical jokes galore and lots of Yarns

- Saloon life and etiquette

- Gambling

- Bad-men and bandits, gunfights, and stage robberies

- Mining

- Financial history and shenanigans

- Journalism, including Mark Twain

- Politics

- Western Terminology

- And sketches of the prominent people of the Comstock Lode and Nevada politics.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

Word of Mouth Revisited

I’ve contended that word of mouth is the greatest marketing

tool available to authors. Word of mouth includes book clubs, online recommendations

at sites like Goodreads and LibraryThing, reader reviews, and good ol’

fashioned face-to-face conversation. Word of mouth does not include anything

the author says, including social media leavings that come from gallivanting

around cyberspace. Potent word of mouth comes unexpectedly from a trusted

source. Every author’s marketing strategy must focus on generating positive

word of mouth.

Recently, I had confirmation of this axiom. In the first of August,

I ran a discount promotion for a couple of days for the e-book version of The Shopkeeper. I don’t believe in

offering free e-books because there is no lasting effect beyond a couple days. Many

people gather up free books and never bother to read them. I’ve discovered that

there is an entirely different dynamic for 99¢

e-books. Evidently this tiny fee motivates people to read the book.

I decided to use a brief

99¢ price for the

first novel in the Steve Dancy Tales

to give a boost to the entire series. It worked far better than I expected. Not

only did The Shopkeeper sell almost two thousand copies, all the other books in

the series showed accelerated sales. Actually, it has been over a month since

the promotion and all five books in the series still sell at more than double

the pace of sales prior to the promotion. Free e-books have no legs, but 99¢ e-books seem to have a

long tail.

None of this was news to me. But I did make an observation

about this promotion that had previously eluded me. If a promotion goes well

and readers like the book, then word of mouth accelerates sales in other

formats and for other books by the same author. I never track audio sales

because they’re small compared to other formats. I kept an eye on them

this time, and I noticed a major surge in sales about a week or so after the promotion.

Print sales also surprisingly increased, and sales of my other books grew

significantly. The additional sales could only come from word of mouth because

none of these other books or formats were discounted or promoted beyond my

normal feeble efforts. People who liked The Shopkeeper told other people about my books. Some marketing gurus tell you to

make fans out of your readers. Good advice, but if you really want to sell lots

of books, turn your readers into your own personal sales force.

How? Write an engaging story that never jerks your reader

out of the story. This means you need to keep the story moving forward, avoid unnecessary

plot detours, and have it all professionally packaged. If you enthrall your

readers, they’ll tell their friends, family, and neighbors about this great new

author they found. After you have a large and growing sales force, you can

concentrate on what you really love to do—write.

Friday, July 25, 2014

Publishing advice for a relative

A relative asked for advice on how to publish a math book he had written. I've included my answers below in the hope it might help other aspiring writers.

I would strongly suggest traditional

publishing for a math book. You are correct that traditional publisher have

access to the proper sales channels. In fact, academia seldom buys

self-published books, so traditional publishing is your best, and possibly

only, option.

Many people

say you must have an agent to traditionally publish. This is true for fiction

and popular nonfiction, but not always required for specialized nonfiction.

Some publishers accept non-agented manuscripts. My suggestion is to seek

an agent and a publisher simultaneously. To find out how to do this, spend a

few hours in a library with Jeff Herman's Guide to Book Publishers, Editors and Literary Agents. Read the

articles about how to write query letters, book proposals, select an

agent/publisher, etc.

Here are a couple of publishing clichés that became clichés because they are often true:

Fiction is published based on the author’s platform, and published nonfiction is based on the author's credentials.

Nonfiction is sold with a book proposal; novels are sold as a complete manuscript.

This means you

should stress your math credentials in your query letter and book proposal.

Book proposal formats vary, but they all include a sample chapter, Table of

Contents, a section on the author, and a section on the target market.

Don’t worry

about a publisher stealing your concepts. Also, if the agent you query is

listed in Herman’s book, you don’t need to be concerned about him or her

stealing your ideas either. You will need to use your judgment with friends and

colleagues.

All of this

means you should not wait until your book is complete to your satisfaction. Hone one chapter until it

is as good as you can make it and include the other sections required in

a book proposal. Then send query letters out to publishers and agents

simultaneously. Don’t send a proposal or manuscript unless you get a positive

response from a query because it will just end up in a slush pile destined to

be read by an intern … someday … perhaps. If you use this approach, you will

have plenty of time to complete the entire book to your satisfaction. In fact,

publishers assume nonfiction books are not complete at the time of contract signing.

A standard clause is a book delivery schedule.

Which brings

us to terms and conditions. The sad truth is that unless you are famous or have

committed a high-profile felony, you have little influence over the T&Cs, which

include royalties. This is true if you negotiate the contract yourself or have

an agent negotiate it on your behalf. These contracts are boilerplate for the

most part. The agent’s job is to secure the biggest advance possible. My agent also

negotiated out a first-rights clause for a second book, but he was able to get

little else. Ancillary rights are demanded by traditional publishers. Wiley

even insisted on the theatrical rights to my computer management book. (I was

thinking of a musical.)

The primary benefit of an agent is to get your manuscript

moved to the top of the pile. Agents also know the interests of different

publishers and can keep you out of cul-de-sacs. If you query publishers directly,

use Herman’s book to select publishers that specialize in your subject or

market.

Nowadays, traditional publishers are paying higher

royalties on e-books, but nowhere near the direct payments to independent

authors. Traditional publishers pay an advance, so they are concerned first with earning back the advance. Indie-authors higher royalties reflect the fact

that they receive no advance and pay publication costs.

Traditional

publishers will take care of “cleaning up a book.” Wiley assigned an editor and

3 line editors to my book. They also insisted on control over the title and

cover. It’s been many years since I published The Digital Organization, and things may have changed, but

basically the publisher calls most of the shots.

As for my

books, if you are interested in history, I recommend Tempest at Dawn. If you like

action/thrillers, then I would recommend The Shopkeeper or The Shut Mouth Society.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)