Charlie Jane Anders wrote a piece for io9 about How

to Write Descriptive Passages Without Boring the Reader or Yourself. Her

article includes some good advice, including:

- Commit to never being boring.

- Engage all five senses.

- Try being super terse.

- Make it dynamic rather than static.

- Make fun of the thing you're describing.

- Project feelings onto an inanimate object.

- Give your POV some visceral or emotional reaction.

- Use less dialogue.

- Use description to set up a punchline in dialogue.

I would add three more for an even dozen:

- Never start a book or chapter with too much description.

- Interleave description in small doses.

- Write about interesting places.

|

| Candelaria (aka Pickhandle Gulch) |

I usually start chapters with action and then intersperse tight paragraphs of description. I prefer delivering description in a single paragraph at a time and

seldom have more than two descriptive paragraphs in a row. I also like to write about interesting places.

Novels will take you to mundane locales, but you can always insert an

interesting detail.

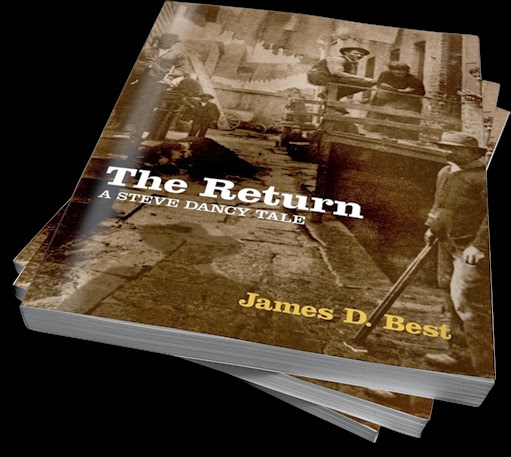

The Steve Dancy Tales start in a Nevada mining camp called

Pickhandle Gulch. I walked the current-day ghost town, fascinated by the miners’

rock igloos. (The town must not have discouraged littering because the mouths of these rock dwellings were strewn

with hundreds of rusted tin cans.)

Here is how I described the camp in The Shopkeeper.

Pickhandle Gulch nestled between the Silver Peak Range and the Excelsior Mountains. The main road curved up a mild grade toward a stamp mill, an ugly building that pulverized rock and made a nerve-racking noise all day long. About two dozen thrown-together buildings lined either side of a road, and hundreds of hovels scarred the surrounding slopes. Miners built these shelters with rocks because the beige hills that rolled off in every direction were completely barren of trees. For that matter, hardly any foliage reached above a man’s boots, and even the valley spread out below presented only a relentless brown landscape spotted with a few rocks and some pale sagebrush. Lumber was the second-dearest commodity in town. Water was the first.

.jpg) |

| Honest westerns ... filled with dishonest characters. |

.jpg)

.jpg)