|

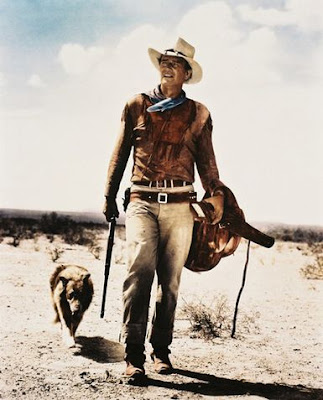

| Hondo by Louis L'Amour |

In 1949, Joseph Campbell published The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Campbell studied myths and stories down through the ages and came up with twelves

steps in a hero’s journey, starting with normalcy or status quo and ending

right back at status quo. The Matthew Winkler animated video illustrates

Campbell’s definition of the journey. Campbell made a brilliant set of observations

about the striking similarities of heroic sagas told throughout time and in

every culture. (Steve Dancy complies with Campbell's theoretical journey.)

Campbell also breaks some new ground in describing the universal need for heroes, albeit in a language foreign to mortals.

The first work of the hero is to retreat from the world scene of secondary effects to those causal zones of the psyche where the difficulties really reside, and there to clarify the difficulties, eradicate them in his own case (i.e., give battle to the nursery demons of his local culture) and break through to the undistorted, direct experience and assimilation of what Jung called “the archetypal images.”

Say what?

The Hero With a Thousand Faces gives the impression that the

journey itself makes the hero. It might be more accurate to say that anyone who

prevails through all of the steps elevates himself or herself to heroic status.

Most people retreat at Step One: Call to Adventure.

I believe heroism is more a question of character than events. Mark Twain agrees with me. He wrote:

I believe heroism is more a question of character than events. Mark Twain agrees with me. He wrote:

“Unconsciously we all have a standard by which we measure other men, and if we examine closely we find that this standard is a very simple one, and is this: we admire them, we envy them, for great qualities we ourselves lack. Hero worship consists in just that. Our heroes are men who do things which we recognize, with regret, and sometimes with a secret shame, that we cannot do. We find not much in ourselves to admire, we are always privately wanting to be like somebody else. If everybody was satisfied with himself, there would be no heroes.”

Raymond Chandler also had a character-driven definition of a

hero:

…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.

He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him.

The story is this man’s adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure. If there were enough like him, the world would be a very safe place to live in, without becoming too dull to be worth living in.Joseph Campbell is popular in academia, but perhaps it's possible to get a better description of a hero by asking one of those storytellers who have passed these tales down from one generation to the next.