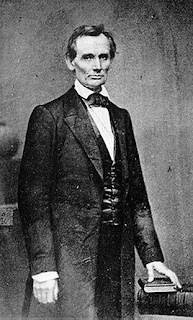

In early 1860,

Abraham Lincoln was a little known regional politician from Springfield,

Illinois. The Republican Party was new, and had failed running national hero

John C. Frémont for president in 1856. Abraham Lincoln chances of ascending to

the presidency under the Republican banner were slight. All that changed in New

York City on February 27, 1860. That afternoon, Lincoln had his photograph

taken by Mathew Brady, and in the evening, he gave a historic speech at the

Cooper Union. Lincoln often said that Brady’s photograph and his Cooper Union

address propelled him to the presidency.

Below is a highly abridged

version of Lincoln’s speech.

“We hear that you

will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that event, you say

you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having

destroyed it will be upon us!

“That is cool. A

highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, ‘Stand and

deliver, or I shall kill you and then you will be a murderer!’

“What the robber

demands of me—my money—is my own; and I have a clear right to keep it; but my

vote is also my own; and the threat of death to me to extort my money and the

threat to destroy the Union to extort my vote can scarcely be distinguished.”

“What will convince

slaveholders that we do not threaten their property? This and this only: cease

to call slavery wrong and join them in calling it right. Silence alone will not

be tolerated—we must place ourselves avowedly with them. We must suppress all

declarations that slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in

pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with

greedy pleasure. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected from all taint of

opposition to slavery before they will cease to believe that all their troubles

proceed from us.

“All they ask, we

can grant, if we think slavery right. All we ask, they can grant if they think

it wrong.

“Right and wrong is

the precise fact upon which depends the whole controversy.

“Thinking it wrong,

as we do, can we yield? Can we cast our votes with their view and against our

own? In view of our moral, social, and political responsibilities, can we do

this?”

The hall burst with

repeated shouts of “No! No!”

“Let us not grope

for some middle ground between right and wrong. Let us not search in vain for a

policy of don’t care on a question about which we do care. Nor let us be

frightened by threats of destruction to the government.”

Prolonged applause

kept Lincoln silent for several minutes before delivering his final sentence.

“Let us have faith

that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our

duty as we understand it!”

When Lincoln stepped

back from the podium after this dramatic conclusion, the Cooper Union Great

Hall exploded with noise and motion. Everybody stood. The staid New York

audience cheered, clapped, and stomped their feet. Many waved handkerchiefs and

hats.

If you want to see

how a principled politician gained national repute with honor and integrity, I recommend Lincoln at Cooper Union by Harold Holzer. You might also enjoy the Lincoln historical theme I used in my contemporary thriller, The Shut Mouth Society.